Grieving in Prison

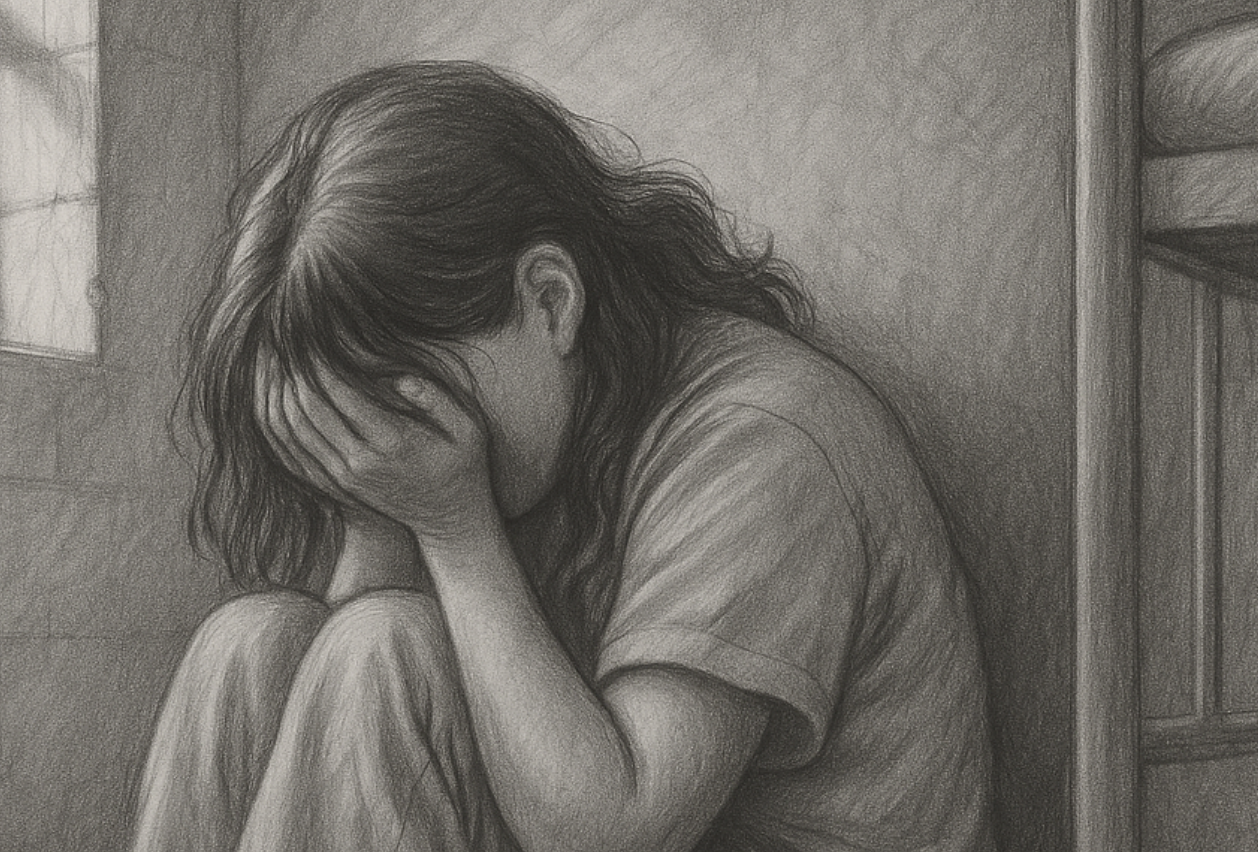

What it means to mourn when no one can hold you.

By Cindy Shepheard

How does one truly grieve while in prison? One doesn't—not fully, not completely.

You may be eligible for a funeral furlough, but that only works if you anticipate the passing well in advance, and if you can afford the fees. The approval process takes a minimum of 30 days. And if it's granted, the individual in custody is required to pay for mileage, gas, and the day wages of the accompanying officers, all in advance. Most applications don’t get approved.

And even if you are granted a furlough, let’s be honest: Who wants to wear shackles, waist chains, and cuffs for hours just to spend 15 minutes with the deceased? You're not allowed to speak with other family or friends. It's just you, your loved one, and two armed correctional officers who may or may not have compassion.

Forgive my cynicism. In 2016, my father passed after a long battle with colon cancer.

I rarely got the chance to see him because he had been too ill to travel, but he surprised me with a visit on my birthday. I spoke with him the Sunday before he died. I told him how much I loved him and assured him that if he was tired, it was okay to get some rest. My mom and I would be fine.

That was in June. My brother hanged himself in September of the same year.

I was just numb. None of it seemed real. I knew they were gone, but when I called, I still expected one of them to answer the phone.

In 2019, my mom was diagnosed with terminal lung disease. She died five years later, in 2024. Illness, old age, and the toll of mourning my father wore her down. She passed away in a state-run nursing home with a nurse sitting beside her, holding her hand.

I have no living siblings. All of my aunts, uncles, and grandparents have passed. Even my few cousins are gone.

I’m sad, angry, beside myself. I want to scream at everyone. I’m heartbroken.

I cry a lot most days.

I’ve been sad before. I’ve shed tears for other family members who passed away. But this time, it broke me. Losing my dad, my brother, and finally my mother. I stopped wearing the mask of my former self.

I couldn’t express this to the mental health staff at Logan. If I did, they would classify me as suicidal and place me naked in a strip cell with a heavy, velcro, suicide-proof canvas smock, with no blanket or toilet paper. This would supposedly be for my safety, so I could not hurt myself. However those actions only exacerbate the pain, loss, and humiliation.

I am not suicidal; I’m in pain. I’m just a small, wounded child who really wants her mom. I want her wisdom. Her laughter. Her understanding. Her life experience. Her silly humor. Her storytelling, even if I already heard the same story a hundred times. I want her.

My mom and I became incredibly close after I was arrested. She was one of the few people who truly believed me and believed in me. She used to say, “I promise I will be there to bring you home.”

So it crushed us both when she finally said, “Honey, I don’t think I’m gonna be able to keep my promise.” But I already knew that.

Her passing has changed the way I see everything. I still hold onto hope—for new laws, for release in the next couple of years. But I carry a sadness I’ve never known before, an emptiness that nothing seems to fill. Will it ever be filled?

Grieving in prison is a challenge most people will never understand. Most days, I just want to be left alone. I don’t eat much or sleep much. Sometimes I shower at 2 a.m. My mind races. I drift through music, TV, and homework, but my focus is shot, like “short attention span theater.”

Fortunately, I have a few people in here who feel like family. I can truly cry with them. Really cry: ugly, snot-nosed, red-faced, swollen-eyes crying.

And despite my grief—or maybe because of it—I know I will make it. I’m Ellen’s daughter. I’m Vickie’s biological daughter.

Ellen Sue Collins, you are so deeply missed. I miss you, Mom.