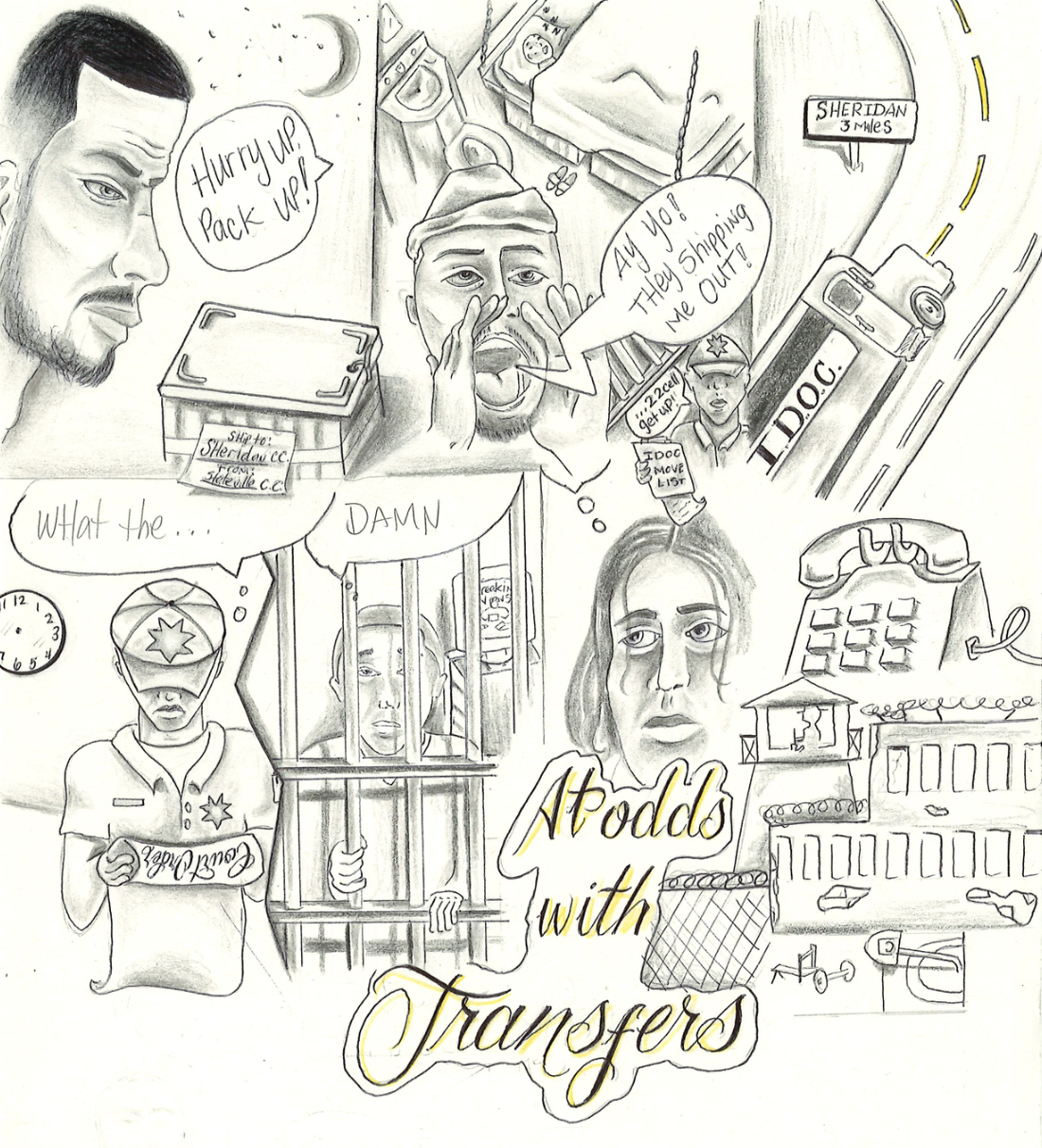

At Odds With Transfers

A commentary on the move from Stateville Correctional Center in 2024.

Story by Fly Miller

Illustration by Ariel Bueno

The Announcement

Boxes were being filled and taped-sealed as individuals in custody at Stateville Correctional Center prepared to transfer out of Stateville for the last time. Sad faces of long timers because, for them, this was their home for the last two to three decades. They had gotten used to the environment: lax security and being close to the city of Chicago where most of the Stateville individuals in custody came from.

2. The Goodbyes

Every Tuesday and Thursday morning around 5 a.m. in late August 2024, transferring individuals in custody would be yelling their farewells to their remaining friends whom they have known, and grown to love, over the last few decades of living behind the walls of Stateville. These were really heartfelt goodbyes. Some of these goodbyes woke others out of their sleep. As the weeks went on, the cell houses became quieter. A population of nearly 500 individuals began to dwindle.

3. The Transfer

Some individuals in custody, such as NPEP and North Park students, knew where they would be going—but for most, there was anxiety and no information. Many were transferred to worse prisons downstate, such as Menard, Pinckneyville, and Lawrence Correctional Centers. These prisons are not only further from families— hundreds of miles and hours of driving away—but also more dangerous.

4. The Anxiety

In 2024, Governor J.B. Pritzker ordered that Stateville Correctional Center be closed because of unsafe living conditions. A federal court also ordered transfers: all individuals in custody (except those in the healthcare unit) had to be moved by September 30, 2024. This created anxiety.

Once prisoners were transferred, they would return to two-man cell living quarters—the size of your average bathroom. Some individuals, like Darrell Fair, favored single-man cells and thought individuals in custody should band together to keep Stateville open.

5. The Discomfort

Some families, like Joseph Eastling’s, wrote and called to request transfers closer to home—but with no success. Joseph was sent to Pinckneyville; within a week, they were on lockdown. I talked to staff who had no idea where they would be transferred. Officers came to me wondering where they would be going. I had no clue.

6. The Aftermath

“Maybe the move saved lives.” That’s what we were told. A federal judge ordered the closure after inspectors found Stateville unsafe: crumbling buildings, contaminated water. Officially, we were now in a better place.

But not everyone felt that way. Transfers tore people from their programs, from families trying to visit, from the stability they’d built. For many, leaving Stateville meant heading farther from home and deeper into unknown dangers.