In Conversation with ... Marquis Bey, Northwestern University Professor of Black Studies

Dr. Marquis Bey's approach to teaching and scholarship through the lenses of race and gender, as told to NPEP student Joyce McGee.

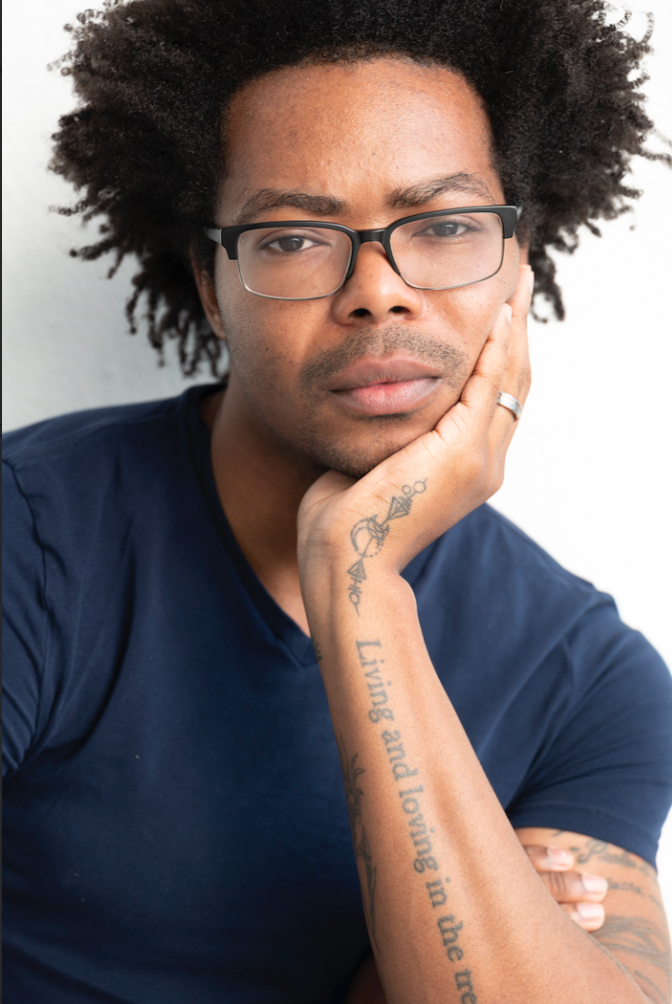

Courtesy of Dr. Marquis Bey

I was blessed to have Dr. Marquis Bey as a professor in spring quarter 2023. He has a very unconventional teaching method, very simple and laid back. He is a fountain of knowledge, and he facilitates the flow of ideas with ease.

I felt so expanded when I left his classroom. Dr. Bey gave real meaning to people like Langston Hughes, bell hooks, and James Baldwin. He introduced me to people like Tim Wise and Eula Biss, and the next think I knew I was dissecting these tough texts on white supremacy and oppression, on marginalized people and sexism and race. Dr. Bey had the entire class captivated. We talked and debated our assumptions and beliefs like true scholars.

I had the opportunity to interview Dr. Bey and get to know him a little more. We explored his journey to becoming a professor, the books and articles he has written, his love for Black history and for teaching—and more. His answers made me feel alive and eager, and they encouraged me to understand more deeply how Black life, Black queer life, and Black femme life can positively impact all lives—which is one of his goals as a professor.

On the following pages are Dr. Bey’s responses, comments, and observations from our interview, edited lightly for length and clarity.

I was born and raised in Philly. I’m a middle child—my brother is three-and-a-half years older than me and my sister is 12 years younger than me. I’ve always been the one who got good grades and liked school. But it wasn’t until late high school/early college that I started loving reading. For me, reading is how I discover, how I tap into a vast history of others who have felt and thought and experienced things like and unlike me. As James Baldwin says, “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive.”

In college, I majored in philosophy, American studies, and English (yes, three majors—I was very, very extra), meaning that I had to ask myself, “What the hell do I want to do with this?” I knew I wanted to write and read and think. So, I went to grad school. I did my Ph.D. in English at Cornell University, and began specializing in Black feminism, queer theory, contemporary Black literature, and critical theory (this is just the cool academic way of saying “philosophy”).

And from there, I just kept reading and writing about these things. And now I’m at Northwestern, in the Black Studies department, Gender and Sexuality Studies program, English department, and Critical Theory program (yup, four different departments—still very, very extra). I’ve written five books and a bunch of articles, too. The specific topic of each book shifts—from more anecdotal and personal to radical political movements to race and gender theory—but overall they all carry the theme of trying to rethink race, gender, and “racialized gender” (the ways that “gender” is never just gender but always wrapped up in perceptions of race, too). In other words, my books are about how do we interrogate the systems that have imposed certain meanings and conditions onto racially and gender marginalized populations, and how can we use the radical traditions of those population—namely Black, feminist, and queer—to imagine an alternative way of life for us all.

I also love Black history, in part because of how multifaceted it is. There is no one “Black history”; there are so many strands, so many lineages. And to me that is so exciting—I get to think alongside people who thought seriously about freedom and how to arrive at it, or people who thought about better worlds. And I get to see the ways that different people converge or diverge from one another intellectually or politically, then to ask why, what conditions led to that split. I find that stuff fascinating. And more specifically, with Black history there is a unique meditation on questions of freedom and identity and belonging that I personally find incredibly rich, more rich than other fields that ask these questions.

What are my goals as a professor? Of course, I want my students to learn new things. But also, more fundamentally, my goal in all of my classes is to get students to love more deeply Black life, Black queer life, and Black femme life. To see how these ways of living can impact positively all of our lives.

I’ve had so many types of students—of course many, many Black students, but also privileged white students who were incredible in thinking through that privilege and, effectively, being down for the struggle; I’ve had non-Black students of color who saw such wonderfully generative connections with their own lives even if the readings didn’t speak directly to them; I’ve had students, too, who didn’t give a shit about the materials, or who might have even been hostile to some of the ideas. So many students. But one of the reasons why I love teaching is because I get to encounter so many different kinds of students. You all bring such interesting insights to the ideas that sometimes I didn’t even think about.

My teaching methods are on the simpler side. The way I think about it, my role in the classroom is only two things: be a fountain of knowledge and facilitate the flow of ideas. That’s it, really. I assign readings that promote thinking in deep ways, that promote interrogating assumptions and beliefs and understandings of the world. And I trust students to read. In the classroom, then, I want only to provide opportunities to fill gaps in understandings by sharing knowledge from the literally thousands of things I’ve read, and then I want to get students talking to one another.

My students sometimes think I have two personalities. On the one hand, my syllabus is strict and has a harsh tone. On the other hand, I’m quite chill, even Zen, in the classroom. I hadn’t really realized this was a thing, but it makes sense.

My syllabus is pretty unwavering and particular about what I expect in the classroom. As many academics say, the syllabus is a document where professors dump their classroom traumas—in other words, this bad experience you had with a student or with a class manifests in you making a policy in your syllabus that tries to prevent that bad experience from occurring again.

And I guess I’ve done something similar: I’ve had bad experiences with students completely misunderstanding the assignments or doing something wildly unexpected that I wasn’t pleased with. So I try to make my syllabus the kind of document that prevents those things from happening.

The chillness in the classroom is just Marquis being Marquis :). I am pretty laid back by nature. I’m not very angry or loud or demanding. I want to have conversations with my students, ask deep, interesting questions. I trust my student deeply—sometimes too much!—so I’m less concerned with whether y’all actually did the reading. I already assume you all did. With that common ground, we can then have conversations about things that impact us, how the ideas from the readings might apply to our lives or might allow us to live life more courageously, fully, informed, etc. I don’t want my students to feel like they have to perform in any particular way; I want you all to feel like you can just have a conversation with me.