Life on the Outside

How NPEP student Brandon Perkins is navigating life after prison—while holding onto the community that helped shape him.

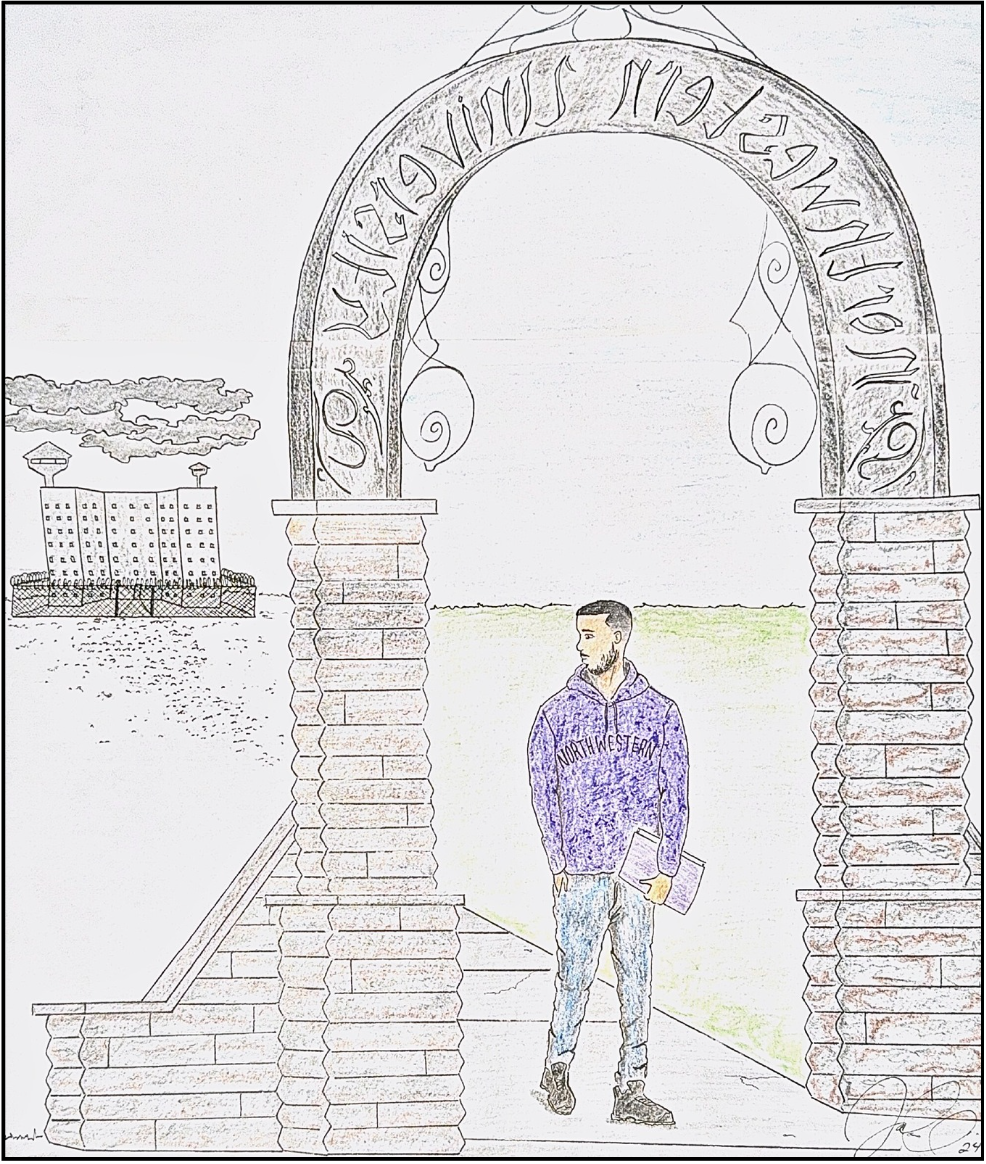

Brandon Perkins walking through the Northwestern Arch (art by Jason Gorham)

By Donnell Green

Brandon Perkins sits in front of his brand-new Mac laptop, dressed in casual jeans, a black Northwestern t-shirt, and warm socks. On this brisk November day, with the temperature at 30 degrees, he has taken refuge inside his home, attending his Northwestern class via Zoom—a stark contrast to being behind bars.

Just weeks ago, Brandon was clad in drab blue prison clothes, navigating plumbing issues and indulging in sugary snacks from the commissary while attending classes at Stateville Correctional Center, where he had been housed for several months. There, he was known for faithfully greeting his classmates with fist bumps and savoring his favorite Now & Laters before class.

Before his incarceration, Brandon made the decision while in Cook County Jail to improve his decision-making and repair some of the harm he had caused. He successfully completed various educational programs and applied to the Northwestern Prison Education Program (NPEP), where he was accepted.

He took classes ranging from The Philosophy of Crime and Punishment to Public Speaking. After mastering his prison routine, he challenged the circuit court for earned “good time” credits that had been withheld from him—and won. Shortly after, he was released. His classmates would no longer receive his Now & Laters, but they celebrated his victory nonetheless.

Brandon immediately received support from NPEP community members to help with his abrupt transition back into society. His newfound freedom presented endless possibilities. Among them, he was able to take part in a long-standing Northwestern tradition: the ceremonial March through the Arch, a rite of passage welcoming freshmen to campus.

Brandon is one of several NPEP students who began their educational journey while incarcerated and continued it while transitioning to life on the outside. I caught up with Brandon on Zoom during one of our class breaks to see how he was balancing his new-found freedom and coursework.

DG: What is the first memory, the first thoughts when you came to prison?

BP: When I got locked up in county, I often thought about taking the trip to prison. It’s something that lingers in your mind in the pretrial stage. To be honest, I was scared of that—this was my first time in Cook County Jail, and it would be my first time going to prison. But, when the time came, I already had six-and-a-half years in county. I wasn’t scared at all; I was relieved because I knew the hard part was over and now I had an out date. I figured nothing could be worse than county, and I knew so many people from being in county for so long that I knew I was bound to run into people no matter what prison I ended up in.

DG: Talk to me about the bonds you’ve built within the NPEP while incarcerated, the strength of those connections, and how it’s been maintaining those connections with your outside community.

BP: The first introduction to the NPEP community was when all the people in my cohort got on the bus. As the bus made its way from southern Illinois toward Stateville, the bus started filling up, and little by little we started making introductions. I knew a few people on the bus, and many other people knew each other too. Then we got to Stateville and met everyone else—the other cohorts, NPEP tutors, volunteers, and staff. Everyone was so welcoming and helpful. The guys were offering help and tutoring, and the outside community was so kind and supportive. We have built lasting relationships, especially within our cohort—we are all pretty cool with each other. The outside NPEP community is so genuine in the way they build relationships. It’s not a transactional relationship; they care and want to help.

DG: Are you allowed to speak with any of your incarcerated classmates?

BP: I’m not allowed to talk to any of the guys in NPEP who are still incarcerated outside the classroom setting. It’s an unfortunate reality because I want to be able to help and be a voice for those that are still inside. Also, I feel we’ve built a connection, and I don’t want to abandon that.

DG: Talk to me about the process of getting rid of your prison schedule, the one you had on the inside, and if you were able to get rid of it.

BP: Getting rid of the prison schedule has been pretty tough. Even when I go out and stay out late, I wake up early the next day. I make my bed up first thing in the morning and get my hygiene together. But it has also been kind of difficult filling the time. Inside, we’re always waiting on something, whether it’s chow, yard, showers, phone time, or school. Out here, you’re on your own time (which is great, no complaints), but it’s made it hard for me to be able to adjust by being disciplined and accountable for myself.

DG: You wrote a paper about the effect prison pain had on you. Talk about some of the emotions you had seeing us on Zoom the first time.

BP: Seeing everyone in class for the first time after being released was kind of surreal. I came from a serious situation and was facing serious charges and walked away with a light sentence. So I think I felt a type of survivor’s remorse—I felt like I left everyone behind. That’s another reason why I would like to keep some communication open with people in there. I know what it’s like when nobody answers calls, and what it’s like talking to people just hearing about what’s going on in the world. Another aspect of that is that I have two co-defendants, a man and a woman. They call me pretty often, and I’m trying to help them get into NPEP, too.

DG: What are some of the things you can do to avoid the triggers of survivor’s guilt?

BP: The only thing I can do to avoid survivor’s guilt is play my part and hope that we can make strides—creating a new narrative, opening up opportunities, and getting people home.

DG: Do you feel any pressure to achieve success on behalf of NPEP students?

BP: I do feel that there is pressure being part of NPEP. Even on campus, I feel like I have to be on my absolute best behavior because I know there are people just waiting to point a finger to say, “I told you so. Those people don’t deserve this opportunity.” In addition, though, I feel like we are an example—every college is looking at us right now, so if we succeed, we open the door for 2 million people who are incarcerated to get a chance at higher education behind bars.

DG: What foods did you miss the most while you were away?

BP: The food I missed the most while I was locked up was my grandma’s food. Unfortunately, she passed in 2017 while I was in Cook County Jail. My mom cooks well too, but nothing beats my grandma’s cooking. Besides that, what I missed are my two favorite things: tacos and pizza! I can eat that stuff every day, and I have been. That’s why I gained so much weight.

DG: What is the first thing you ate when you got out?

BP: The first thing I ate when I was released was some BBQ food from this really good family-run spot by my house. Ironically, I saw a C.O. from the county there. I felt like I couldn’t escape these people.

DG: I know that you’re a mama’s boy, is there anything you want to say to your mom?

BP: Yeah, I am a mama’s boy. Haha. I just want to thank her for supporting me and going through this difficult journey with me.